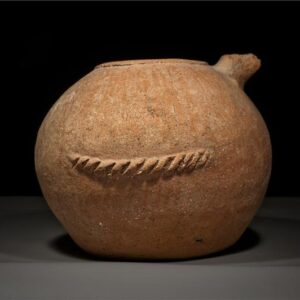

This remarkable and rare object is a Bronze-Age snake shrine from ancient Canaan. It bears a superficial resemblance to a Chalcolithic funerary urn but it in fact a devotional piece which reflects a cultic affiliation to snakes which is technically known as ophiolatry. It is shaped in the form of a long barrel vault, sealed at one end and open at the other. The open end is surrounded by a quadrangular façade which is considerably taller than the main body of the piece. Unlike the body, which is plain, the portions of the façade above and below the entrance are decorated with a series of curvilinear, serpentine designs that frame the doorway (four above and one beneath).

The precise function of these pieces is not clearly understood, but there are indications that they contained an actual snake and/or offrenda dedicated to them, in a religious/ritual setting such as a chapel or perhaps prosperous domestic setting. The ancient populations of the Middle East and Northern Africa believed snakes to be sacred and holy due to their apparent immortality in shedding their skins and emerging ‘reborn’. As a result, various cults and devotional institutions dedicated to snakes sprang up from Mesopotamia to Canaan, as well as further afield in Crete and even Nubia, where the tradition is believed to have originated. Materials dedicated to this practice of worship have been found at many sites, notably including Megiddo, Shechem and Hazor. Later incarnations of the faith have been found in northern Syria (Hittite), at the Assyrian site of Tepe Gawra and also in 6th century B.C.E. Babylon.

Devotional items usually take the form of bronze or copper snake models, sculptures of humans holding snakes, offering stands decorated with snakes, or items such as this. There is a stylistic trend from the Nubian model – tall, slim temples dating to around 3000 B.C.E. – down to more ornate examples in Megiddo and Beth She’an (c. 1500 B.C.E.) and more flamboyant shrines appearing in Crete towards the end of the 2nd millennium B.C.E. The style of this example is traditionally Canaanite – well formed and structurally complex yet superficially simple, providing a harmonious and well-proportioned composition.

The Canaanites were one of the ‘tribal’ groups of what was to become Israel, Palestine and Jordan, who had their cultural roots in the Neolithic revolution when agriculture revolutionised Near East economics. By the Bronze Age the stability of the area and their position between great trading powers – notably Egypt and Mesopotamia – made them prosperous and culturally diverse, and was a high point for artistic creation. The culture contracted with economic issues suffered by Egypt and the Mesopotamians, and went through a collapse at the end of the Bronze Age due to a combination of ‘Sea People’ invasions, environmental meltdown and internal troubles in Egypt leading to loss of infrastructure throughout the Near East. Their resurgence of power in the Iron Age was matched by that of the Ammonites and Moabites, among others, and the region eventually came under control of the Neo-Assyrians by the mid 8th century B.C.E. Yet it is earlier pieces which retain this uniquely harmonious form and style. This is an attractive and elegant piece of ancient art.